The concept behind this set of postcards - one featuring species commonly found in Long Island bays and another set in New York's Great Lakes ecosystem - is to generate interest in New York Sea Grant's news, events and initiatives via this Web site, nyseagrant.org, as well as through our program's social media platforms - Facebook, Twitter, RSS news feeds, and YouTube. Each postcard also serves as a companion piece to its respective ecosystem poster for the Long Island Bays and in New York's Great Lakes.

And now that the various fish in both scenes have discovered how easy it is to "Get Social with Sea Grant," they're sure to share the newly-learned news bites with their respective schools of fish, bolstering the idea of a "multiplier effect" method in education.

So, like the fish in Long Island's bays and New York's Great Lakes ecosystem, swim around our site and social media platforms and learn more about New York Sea Grant.

New York Sea Grant (NYSG) is a statewide network of integrated research, education, and extension services promoting the coastal economic vitality, environmental sustainability and citizen awareness about the State’s marine and Great Lakes resources. NYSG, one of 32 university-based programs under the National Sea Grant College Program of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), is a cooperative program of the State University of New York and Cornell University.

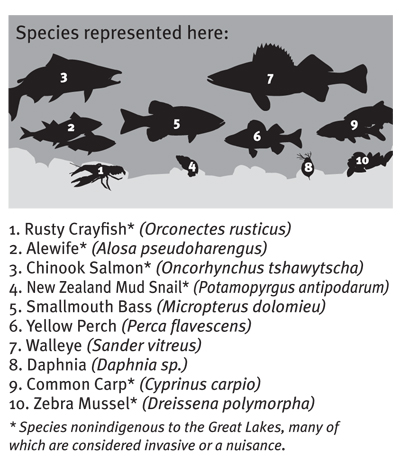

More about the species featured in this postcard:

Rusty Crayfish* (Orconectes rusticus)

Although native to the Ohio River basin and the states of Ohio and Kentucky, rusty crayfish continue to spread into many lakes and streams where they cause a variety of ecological problems. They have invaded much of Minnesota, Wisconsin, Michigan, Illinois, Ontario, and portions of 17 other states, including New York.

They are probably spread by non-resident anglers who bring them along to use as fishing bait. As rusty crayfish populations increase in many areas, they are harvested for the regional bait market, biological supply companies, and food. Such activities probably help spread the species farther. Invading rusty crayfish frequently: (a) displace native crayfish, (b) reduce the amount and kinds of aquatic plants, (c) decrease the density and variety of invertebrates (animals lacking a backbone), and (d) reduce some fish populations.

Environmentally sound ways to eradicate introduced populations of rusty crayfish have not been developed, and none are likely in the near future. Preventing or slowing the spread of rusty crayfish into new waters is the best way to prevent the ecological problems they cause.

Alewife* (Alosa pseudoharengus)

Alewife, a small, silvery fish is the main forage fish of economically-important sportfish species such as Chinook salmon and other salmonids in Lake Ontario. The relatively high abundance of alewife is the reason for the faster growth of Lake Ontario salmon compared to those in other Great Lakes. Data on the abundance of this key prey species are used by management agencies such as the NYSDEC and US Fish and Wildlife Service to help set sustainable stocking levels for a variety of salmon and trout species. In recent years, NYSG research has shown that the alewife may be switching from a diet consisting primarily of zooplankton to one that also includes the opossum shrimp, Mysis relicta, a small shrimp that feeds on zooplankton. The alewife benefits from this addition to its diet; the opossum shrimp’s high content of unsaturated fatty acids is beneficial for the alewife’s successful overwinter survival.

Chinook Salmon* (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha)

Chinook is one of six species of salmon stocked in Lake Ontario by New York State and province of Ontario. The others are: Atlantic and coho salmon, and lake, rainbow, and brown trouts. Adjusting stocking levels can be a sensitive issue for some, though, especially recreational fishermen. Because Mother Nature is in the driver’s seat when it comes to many of the lake’s ecosystem changes – those brought on by reductions in nutrient levels or by the actions of zebra mussels and other aquatic invaders – NYSG's Great Lakes Fisheries Specialist Dave MacNeill says, “adjustment of stocking rates is one of the few management options that fisheries managers can utilize in an effort to manage the lake. But, the effect is at the whim of nature.”

New Zealand Mud Snail* (Potamopyrgus antipodarum)

New Zealand mudsnails are tiny invasive snails that threaten the food webs of trout streams and other waters. Native to New Zealand, they were first found in Idaho’s Snake River in 1987. They quickly spread to other Western rivers, sometimes reaching densities over 500,000 per square meter. In the Great Lakes, mudsnails were first found in Lake Ontario in the early 1990s. In 2001, they were found in Lake Superior in Thunder Bay, Ontario, and in 2005 in the Duluth-Superior Harbor, likely spread by ballast water discharged from ships.

Anglers pose a risk for spreading New Zealand mudsnails because they can be moved on waders and gear. They can close their shells allowing them to survive out of water for days. One snail can reproduce and start a new infestation. Eradicating infestations is nearly impossible. Your help in detecting and reporting new infestations is vital for preventing their spread.

Smallmouth Bass (Micropterus dolomieu)

Known commonly by several names - northern smallmouth bass, black bass, brown bass, white or mountain trout - this species can be found throughout the Great Lakes waters, including Lakes Ontario and Erie. Their average sizes can differ, depending on where they are found, with males being generally smaller than females. Their habitat plays a significant role in their color, weight, and shape. River water smallmouth that live among dark water tend to be rather torpedo shaped and very dark brown in order to be more efficient for feeding. Lakeside smallmouth bass however, that live for example in sandy areas, tend to be a light yellow brown to adapt to the environment in a defensive state and are more oval shaped.

Yellow Perch (Perca flavescens)

Yellow perch are found in many habitats including shallow vegetated areas of ponds, lakes and streams where they move in large, loosely organized groups called “schools.” Above all, they favor the habitat provided by weedy, warm water lakes. Zooplankton is a primary food source for yellow perch and other sportfish, including walleye and alewife. In addition to adult yellow perch being a food source for humans, young perch are a crucial part of the aquatic food web. Yellow perch are an important forage fish, or food source, for salmon and many other larger game fish species.

Walleye (Sander vitreus)

In the wild, walleye feed exclusively on living organisms, such as zooplankton, insects, and other fish. They have excellent night vision and tend to feed when light levels are low, such as at dawn, dusk, and before rainstorms. Though, in very turbid water, they may be active during the day as well. Walleye can tolerate a wide range of physical and chemical conditions, such as relatively low dissolved oxygen levels. This species prefers to spawn in shallow (3-12 inches), clean, hard-bottomed areas with rocky cobble and gravel areas. As noted in a NYSG Great Lakes fisheries fact sheet series, their habitat can be damaged by siltation from stream bank erosion in an agricultural stream crossing.

Daphnia (Daphnia sp.)

Daphnia and other small plankton also serve as food for young fish. Since the late 1990's invasion of the nearly microscopic fishhook water flea in New York's Lakes Ontario and Erie and Finger Lakes waters, there has been a decline in the abundance of Daphnia and other dominant zooplankton. This makes the fishhook water flea a viable competitor with fish relying on Daphnia and other zooplankton species as a food source, such as alewife and rainbow smelt.

Common Carp* (Cyprinus carpio)

The common carp, found in the Great Lakes today, comes from the Caspian Sea and parts of Asia. The carp was originally stocked in the basin in the late 1800s by the U.S. Fish Commission as a source of “cheap” food for the future (carp quickly fell out of favor as a food species). The fish were commonly stocked in farm ponds where they often escaped into nearby ecosystems during periods of flooding. Once released into the Great Lakes Basin, carp spread quickly and easily – in fact, the common carp can now be found in every state in the continental U.S.

The common carp is a very hardy fish, capable of surviving in less than optimal habitats. They are also prolific breeders, inflicting substantial competition for habitat on other, more desirable species.

Zebra Mussel* (Dreissena polymorpha)

During the late 1980s, zebra and quagga mussels were introduced into the Great Lakes as veligers (larvae) from freshwater ballast discharged from freighters that originated in the Black and Caspian Sea regions of eastern Europe and western Asia. These small, bivalve mussels have the ability to filter huge amounts of water (up to two liters per day per adult mussel) in order to draw in the plankton they use as food. Zebra and quagga mussels primarily consume phytoplankton (microscopic plant life) which forms the base of the aquatic food chain, although they can also consume small zooplankton (tiny aquatic animals) and bacteria. This filtering, and subsequent removal of plankton from the lakes, has created a dramatic increase in water clarity. Although the clearer lake water is seen as an aesthetic benefit to some, the loss of nutrients it represents significantly reduces the food that is available for fish and other organisms.

* Species nonindigenous to the Great Lakes, many of which are considered invasive or a nuisance.

A sample of some related NYSG articles and fact sheets include:

- Fact Sheet Series: Showcasing Diversity of Eastern Lake Ontario Region (click here)

- Fact Sheet Series: Encouraging Great Lakes Fisheries Habitat Projects (click here)

- Fact Sheet: Invasive Species of Lakes Erie and Ontario (pdf)

- A Guide to Fish Invaders of the Great Lakes Region. 2008. Sea Grant programs in New York, Michigan, Illinois-Indiana, Ohio, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin have partnered to create training curricula materials centered around the AIS-HACCP concept. The guide includes full-color illustrations for 38 invasive and common look-a-like native fishes. For more, click here or request copies through New York Sea Grant at 631-632-6905.

- Coastlines, Fall '10: Researchers Identify Ways to Improve Lake Ontario Sportfishing (pdf)

- Coastlines, Fall '10: A WWWeb of Lake Ontario Learning (pdf)

- Coastlines, Spring '09: These Scholars Follow the Fish (pdf)

- Coastlines, Spring '08: Great Lakes Tale: The Alewife and the Opossum Shrimp (pdf)

- Coastlines, Fall '06: Spotlight on the Salmon River (pdf)

- Coastlines, Fall '04: Big Fish, Little Fish (pdf)

- Coastlines, Spring '04: Little Critters, Big Impacts (pdf)

- Coastlines, Summer '03: Taking Stock of Stocking (pdf)

For additional information about the species represented here, check out the following Web resources: