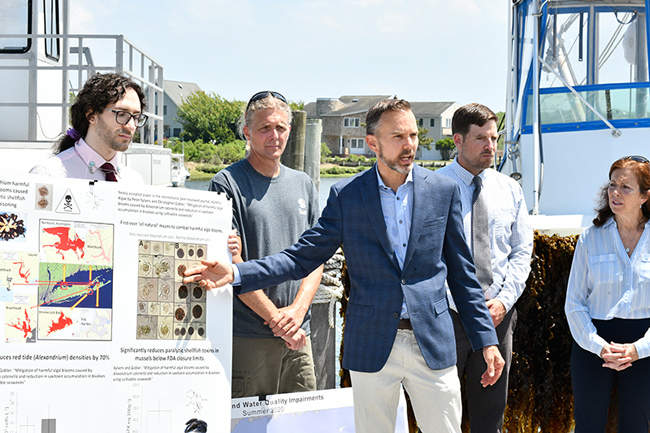

Christopher Gobler, Ph.D, announced May 27, that a species kelp can significantly reduce nitrogen levels in the water. Credit: Dana Shaw

NOTE: Using kelp to help reduce nitrogen in Long Island waters was the subject of Dr. Christopher Gobler's May 27th press conference at the School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences (SoMAS) Marine Science Center at Stony Brook Southampton. This research was sponsored by Suffolk County, New York Sea Grant, the New York Farm Viability Institute, and USDA. Below is a media mention related to this announcement.

— Filed by Michael Wright for Sag Harbor Express

Southampton, NY, June 2, 2021 - Scientists from Stony Brook University say that a species of seaweed native to the East End coastline may prove to be an important weapon in the fight to overcome pollution problems from decades of overdevelopment and negligent environmental policies.

Sugar kelp, a brown rubbery plant that can grow underwater fronds up to 15 feet long, is proving in test cases, the researchers say, to be highly efficient at soaking up nitrogen and phosphorous in tidal waters; can be sold for use as food, cosmetics ingredients or processed into highly effective organic fertilizer; and appears to even be particularly deadly to one of the most toxic species of “red tide” algae found in local waters.

Growing kelp in tandem with mariculture farms, where oysters are grown in submerged cages suspended from floating buoys, is being seen by scientists, shellfish growers and environmental advocates as a dual benefit opportunity to both combat water quality degradation and introduce a new economic resources for those earning their living on local waters.

Sugar kelp, a brown rubbery plant that can grow underwater fronds 15 feet long, is proving in test cases, the researchers say, to be highly efficient at soaking up nitrogen and phosphorous from the water. Credit: Dana Shaw

Hair-thin kelp seedlings can be attached to submerged ropes in early winter and by spring will have grown into thick, long fronds rich in nutrients soaked up from the water that is then easily harvested and repurposed.

A small area of kelp grown in the bays can absorb as much nitrogen as several of the new I/A septic systems — which can cost $20,000 to $40,000 to install at a home — will remove from the water flushed down a toilet.

“If you had a 1-acre oyster farm, you could mitigate about 20 homes worth of nitrogen advanced septic systems,” said Dr. Christopher Gobler, who leads the team of Stony Brook researchers that have been exploring the possible benefits of kelp growing with experimental farms in the Great South Bay, Peconic Bay and Long Island Sound. “Most of the fronds have gotten from 4- to 6-feet long and can weigh as much as 10 pounds per foot — that’s a lot of biomass you get. And it grows fast, we put it in in December, but it really doesn’t start growing until February, and we’re pulling it out now and it’s grown that much.”

Dr. Gobler’s research team grew and is harvesting nearly 10,000 pounds of kelp on five test “farms” in Moriches Bay, Great South Bay, Peconic Bay and in Long Island Sound this winter.

The kelp they grew is being used in their ongoing research into possible uses for the harvested plants. Dr. Gobler said that they have produced both liquid an dried organic fertilizers from the kelp fronds that is proving to be just as good at sparking growth in plants and vegetables as fertilizers like MiracleGro made with synthetic nutrients. Given sufficient supply of kelp, the organic fertilizer itself could be a commercial venture, he said, and would be a vast improvement over the use of chemical fertilizers in an environmental sense as well.

And, Dr. Gobler said, his lab’s research with the kelp has also revealed that sugar kelp itself appears to contain compounds that are lethal to Alexandrium, a species of red algae that naturally gives off a toxin that can infect shellfish that has sickened or even killed some people who consumed shellfish harvested from waters where the algae was blooming. It has been seen in western Shinnecock Bay and Sag Harbor Cove on numerous occasions over the last several years.

In lab experiments the scientists found that where kelp is grown, the cells of Alexandrium are reduced and if shellfish are growing nearby they accumulate less of the toxin the algae gives off.

The university and the Peconic BayKeeper announced last week that they are hoping to kickstart a “nitrogen credits” program that would incentivize the private sector to pay oyster growers for kelp on their oyster farms. The two organizations are seeding the effort, paying growers $100 for each equivalent pound of nitrogen removed from local waters. A typical home injects about 20 pounds of nitrogen into groundwater per year.

“We want to show that this is a viable crop, but the market is still fumbling to figure out what to do with it, so we want to make sure these farmers continue growing and harvesting the kelp,” Peconic Baykeeper Peter Topping said this week. “The long term idea is that the private sectors will buy in.”

“We see it like carbon credits program: people who want their home or business to be nitrogen neutral, we can do a nitrogen audit of their home or business or even a farm that shows how much nitrogen they are releasing into the environment and they could offset that by paying for X-acres of kelp to be farmed,” Dr. Gobler added.

The veteran scientist — whom Suffolk County Executive Steve Bellone calls “the Paul Revere of water quality” for Dr. Gobler’s role in sounding the alarm about the impact that residential septic systems were having on the Long Island environment — said that the addition of marketable kelp to the business model of oyster farming will hopefully be an incentive to expand both and anchor the idea of “sustainable, restorative aquaculture,” as he calls it.

“There is a lot of room to grow in the aquaculture industry and each farm is removing nitrogen and removing phosphorous and removing carbon dioxide and adding oxygen,” he said. “The beauty of aquaculture is it really can’t collapse like a wild fish stock. You’re only pulling out what you put in. And for every bag of compost or fertilizer we can make from seaweed grown in local bays, you are replacing a bag of Scott’s or whatever that’s coming by truck from Ohio.”

Mr. Topping noted that for all the efforts Suffolk County has made in the last several years to reverse decades of negligent pro-development policymaking by government leaders, it will take decades for “legacy” nutrient pollution of slow-flowing groundwater tables to work its way out of the system. Having a resource for actually removing nitrogen that is already in they system is a completely new tool.

“Mother nature is this natural system: the trees are your frontline defense, then the marsh grasses that filter runoff, but once it’s in the water, it can only be taken up by aquatic plantlife, and we have lost most of our aquatic grasses,” he said. “Mother Nature doesn’t like a wasted resource, so we end up with these algae blooms. We know the I/A systems work on the land, but we have very few options once the nutrient loading has reached the bays.”

State Assemblyman Fred W. Thiele Jr. and State Senator Anthony Palumbo have introduced bills that would make it legal for oyster growers to also use their aquaculture gear to grow kelp as a commercial harvest, and Mr. Thiele said last week that he is buoyed by the hope for a new economic resource that is also an effective weapon in the fight against algae blooms.

“There’s no one single bullet, we have to do a whole host of things,” he said during a press conference hosted by Stony Brook University School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences and the Stony Brook-Southampton Marine Science Center on Thursday. “It’s these efforts that are making a difference in trying to improve water quality, which is critical not only to the environment of the East End but also the economy. We often say here on the East End that the environment and the economy are the same thing.”

More Info: New York Sea Grant

New York Sea Grant (NYSG), a cooperative program of Cornell University

and the State University of New York (SUNY), is one of 34 university-based

programs under the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s

National Sea Grant College Program.

Since 1971, NYSG has represented a statewide network of integrated

research, education and extension services promoting coastal community

economic vitality, environmental sustainability and citizen awareness

and understanding about the State’s marine and Great Lakes resources.

Through NYSG’s efforts, the combined talents of university scientists

and extension specialists help develop and transfer science-based

information to many coastal user groups—businesses and industries,

federal, state and local government decision-makers and agency managers,

educators, the media and the interested public.

The program maintains Great Lakes offices at Cornell University, SUNY

Buffalo, SUNY Oswego and the Wayne County Cooperative Extension office

in Newark. In the State's marine waters, NYSG has offices at Stony Brook

University in Long Island, Brooklyn College and Cornell Cooperative

Extension in NYC and Kingston in the Hudson Valley.

For updates on Sea Grant activities: www.nyseagrant.org has RSS, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube links. NYSG offers a free e-list sign up via www.nyseagrant.org/nycoastlines for its flagship publication, NY Coastlines/Currents, which is published quarterly.